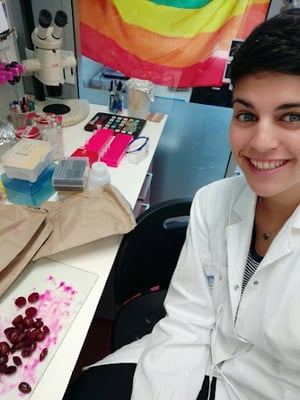

Or Gross is the lab manager of the DeMalach Lab in The Faculty of Agriculture at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The DeMalach Lab studies competition and biodiversity in plant communities, focusing on the annual plant communities growing on the Hamra (red-sandy) soils of the Israeli coastal plain. Their bigger mission is to understand how to efficiently protect endangered species and restore plant communities of the Hamra soil by providing insights into more effective restoration plans.

Or is also the founder of the LGBTQ+ Association at the Weizmann Institute of Science and an activist for queer rights. She uses she/her pronouns and identifies as non-binary, bisexual/pansexual, and lesbian.How did your journey for queer visibility begin?

When I started my bachelor’s degree at the Faculty of Agriculture, I knew almost nothing about my identity. I was quite a high-profile person at the faculty — I have a habit of taking leadership roles upon myself, so I was in the Students Association, I fought for the rights of women and other marginalized groups and I was very vocal and active about the students’ needs. People knew my name even if they didn’t know me personally. And yet, I never paused to ask myself what I really wanted and needed.

Academia did little to inspire my realization — there was hardly any LGBTQ+ presence on campus, and the LGBTQ+ association consisted of four to five people who would meet in a bar once in a while, with no funding or support.

My realization of my identity came quite suddenly, during the second year of my bachelor’s degree. Almost out of the blue, I fell for a woman. Surprisingly, she turned out to be queer as well, but she was in a relationship. After that, I didn’t even think twice — I simply started dating women.

You’d think that would be the end of it, but coming out was a complicated process. The fact that many people on campus knew me made my coming out more of an issue, and I was worried about the reactions I would receive and the potential social and academic consequences.

After quite a long and complicated process, I was finally out at the Weizmann Institute, where I did my Master’s. After I was out, I was able to walk proudly in the corridors, and the establishment of the WIS LGBTQ+ association became possible. In a way, I wanted to create a support circle for people like me, who were ambivalent about being out at their labs and general work environment.

How did people react?

Some people told me that it was “too late” and that I was “late-blooming”, or that it was “just a phase”. I was only 26, but the popular narrative in the straight world is that queer people have always known about their identity when they were children or young teenagers. People tend to question the validity of your identity or simply not believe you if you come out later in life.

Some people told me that it was “too late” and that I was “late-blooming”, or that it was “just a phase”. I was only 26, but the popular narrative in the straight world is that queer people have always known about their identity when they were children or young teenagers. People tend to question the validity of your identity or simply not believe you if you come out later in life.

People would also ask me what were the “signs”, as if they needed “proof” that I was really queer. They viewed the fact that I’ve dated men before as contradictory to my coming out.

Generally, though, I didn’t experience any outright hostility. Mostly, I felt that LGBTQ+ issues were covered up and tucked away in my academic environment. People didn’t talk about it openly, and it was almost like a taboo.

I felt like there was a void when it came to LGBTQ+ visibility, and that’s why I decided to found the LGBTQ+ Association.

Did people come?

Surprisingly, yes. When I established the association, I thought that no one would come, because I barely knew anyone on campus who was out of the closet. But then, on the first meeting, it was like a flood of mice coming out of their holes. It was crazy. So many people came, some of them people that I already knew. Some of them worked at a more religious lab, some of them were scared of being judged, others weren’t out to their families and were scared to tell their lab and PI for fear that they’d be outed. Every time we met, I’d stand at the door and “guard” it until everyone was inside, then lock the door and shut the blinds. It was in the evening when the Institute was relatively quiet, but people were still hesitant.

I knew that it was important work. The Association made people feel less alone. We raised the issue of queer rights and acceptance on campus by organizing pride events, lectures on LGBTQ+ topics for students and staff, and more.

How is the atmosphere at your current lab?

As a lab manager, I have a huge say on who would be part of the lab, and make hiring decisions with diversity in mind. and maintain a very diverse and welcoming lab. I have a pride flag and a trans flag in my office and declared it a safe space for people from the entire campus to come and talk. Additionally, I’m responsible for the welfare of my lab members and they often come to me for advice or to share their feelings. I am happy to be able to make everyone who comes to the lab feel valid and seen.

"I am happy to be able to make everyone who comes to the lab feel valid and seen."

How do you think we can make sure that LGBTQ+ people feel safe in academia?

There’s this misconception that the world of academia, being progressive and enlightened, would be very accepting and aware of issues of representation. Ultimately, however, it’s not much better than any other work environment.

As to how we can make it more welcoming — first of all, I think having an LGBTQ+ Association on campus is crucial for queer visibility and for queer people on campus to feel that they have support. Secondly, I think organizing lectures about LGBTQ topics can be really helpful — especially about the transgender community. People know about gays and lesbians, some even know that bisexuality is a thing, but most have close to zero understanding of trans identities. One time, as an initiative of the LGBTQ association, I invited a trans woman who was a medical student to talk about the challenges that queer and trans people meet when seeking medical help. It was really fascinating and beneficial to everyone who attended. I think this is the best approach — personal stories combined with informative content related to science. It could even be an open, non-mandatory event. I believe a lot of people in academia would be interested in listening and learning. The mere act of inviting such a lecture goes a long way to show that you’re willing to support your queer students and peers.

Do you think LGBTQ+ higher-ups in academia should come out of the closet to provide a personal example?

I feel a responsibility to be out of the closet at work and on campus because I feel like this representation is super important for younger people: Bachelor’s students, people searching for labs for their Master’s or Ph.D., etc. But, I absolutely understand people who do not feel comfortable doing the same. Coming out can be terrifying and sometimes even dangerous — you never know what kind of reactions you will receive. I deeply appreciate it when people use their power and privilege to create visibility and build safe spaces around themselves for others who don’t have such power and privilege. But nobody should feel pressured to come out before they feel it’s right for them. In my opinion, you’re not cowardly or irresponsible or “less queer” for staying in the closet. Your safety and well-being should come first.

How would you recommend a PI, lab manager, or anyone else in a position of power to make their lab an LGBTQ-safe space?

Hang a small pride flag or put a sticker at the entrance of your lab and in your office. People are often reluctant about doing this because they’re afraid it’ll mark them as part of the community or suggest that they’re not straight, and I wish they’d realize there’s no shame in showing that you’re an ally. It’s such a small thing, but it can mean the world to other people. Imagine a student or new employee considering applying to your lab and seeing the pride flag at the entrance. It’s saying loud and clear that they’ll be welcome.

Additionally – connect with the LGBTQ association on your campus and ask them what they need and how you can help. Talk about collaboration and lectures, and let them know what would interest you.

Consider holding lectures at your lab or workplace. As I mentioned earlier, I recommend looking for lectures that are both educational and include a personal story.

“Hang a small pride flag or sticker at the entrance to your lab and in your office... It’s such a small thing, but it can mean the world.”

What would you say to young LGBTQ+ people reading this who are just starting out in the world of science?

Find your support system. If there’s an LGBTQ+ association on your campus, consider joining it. If you don’t have that, find someone who has been in academia for a while and is willing to listen and support you. Tell your friends and family about your hardships. Usually, there’s also some form of subsidized social services on campus that you can contact for support. Generally, just don’t be alone with it.

To summarize — why is queer visibility in science important?

Scientific fields tend to be very competitive and strict, and it’s not common for people to talk openly about their personal lives. It’s also a very male-dominated field. All of this together leads to the environment being if not unwelcoming, then at least cold towards LGBTQ+ people and other marginalized groups. By normalizing queer people’s existence, we can make a real difference for everyone in this field, encouraging people to be more open and adding color and sparkle to our work environments. Creating more inclusive labs leads to better and more creative research since each person has a different point of view and background. Ultimately, promoting queer visibility helps straight people as well, because it opens a gate to normalizing other struggles like mental health issues, disabilities, and more.

We all deserve to have an equal chance of success. So we will continue to lead the fight for equality and inclusion, to make academia a better place for everybody.

This interview was brought to you by Labguru, an all-in-one lab informatics and ELN cloud solution. Labguru views and practices diversity and equality in science as a core value.

To learn more about Labguru

%20(4).png)